necrosis

What is necrosis?

Necrosis refers to the pathological, i.e. pathological, destruction of cells, cell groups or tissue. The DNA clumps and swells within a cell. The cell bursts and cellular components are released, which cause inflammation in the surrounding tissue. Necrosis can be caused by many different influencing factors, such as extreme temperatures, toxins, circulatory disorders, radiation, infections with pathogens or mechanical influences. Necrotic tissue is either replaced by the original tissue (heals) or scar tissue is created.

Concomitant symptoms

The main symptom of necrosis is the externally visible yellowish-black discoloration of the skin. In addition to this usually very impressive symptom, other complaints can occur which confirm the suspicion.

In the case of necrosis, the death and bursting of cells lead to the release of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF). This leads to an inflammatory reaction in the surrounding tissue. This can lead to reddish swelling, pain, tightness and a feeling of warmth around the necrosis. The entry of pathogens, for example bacteria, can liquefy the necrosis and release wound secretions and pus. If the pathogens spread into the blood system and have a systemic effect on the body, fever, chills, nausea and vomiting can also occur. The latter symptoms can be observed in particular with necrosis of the internal organs, such as the gallbladder, pancreas or the appendix (appendix).

Pain

Whether and how severe pain occurs with necrosis depends on the cause and the respective patient. In acute necrosis, for example due to a sudden vascular occlusion in the leg or necrosis of the abdominal organs, there is usually severe pain in the affected area. The main reason is the acute lack of oxygen. In the case of chronically progressive diseases or with a necrotic pressure ulcer, the pain is often so slight that the necrosis is not even noticed. This is mainly due to the fact that the necrosis begins very slowly and the patients often have a reduced sensation in the skin (for example in diabetes).

Causes of necrosis

Necrosis can result from aseptic and septic influences.

The aseptic include, above all, mechanical events, circulatory disorders, radiation damage, poisons, and thermal changes (e.g. frostbite). Circulatory disorders arise, for example, from diabetes, smoking, alcohol consumption, genetic factors or the long-term use of medication.

Septic necrosis is caused by infections with pathogens such as bacteria, viruses and fungi. Each of the causes mentioned causes cell damage in an individual way. The cell reacts to the influencing factor and swells. The cell bursts and the cellular components are released. These trigger inflammation in the surrounding tissue, which leads to the release of inflammatory factors. This causes the tissue to swell and hurt. The inflammatory factors can also lead to the death of other cells, which increases the necrosis.

Pressure ulcer necrosis

A decubitus ulcer is a poorly healing wound caused by immobility and insufficient positioning. Pressure ulcers are commonly seen in bedridden patients. These lie mainly on the back, which creates increased pressure, for example at the level of the tailbone. The sustained pressure results in an undersupply of the area with blood and thus with oxygen. The tissue becomes acidic (acidic) and necroses develop. Often a pressure ulcer is not noticed in time and so-called ulcers (deep wounds) occur. The longer the pressure sore is subjected to pressure, the larger the wound in diameter and depth. Since a pressure ulcer does not heal very well, it is particularly important to turn bedridden patients every few hours in order to achieve optimal positioning.

Read more on the subject at: Pressure ulcer

Necrosis due to osteochrondrosis dissecans

In osteochondrosis dissecans, joint-forming bone tissue dies, which can subsequently lead to a detachment of the bone fragment and the adjacent articular cartilage. Osteochondrosis often occurs in children and adolescents and is probably caused by traumatic influences or by sudden use of the respective joint (e.g. through frequent jumping). The knee joint is most frequently affected, as this is usually exposed to the greatest stress. The therapy of osteochondrosis dissecans depends on the age of the patient, the stage, the joint and the respective anatomical conditions.

Read more on the subject at: Osteochondrosis dissecans

Necrosis after radiation

With iatrogenic (medically induced) radiation, for example in tumor therapy, the ionizing radiation can cause so-called radiation necrosis or radionecrosis. However, one speaks of radiation necrosis above all if it affects healthy tissue, since the tumor tissue was deliberately dying off and therefore does not represent a complication. The ionizing radiation can damage the DNA of the cells, causing them to die and result in necrosis. It is important that such radionecrosis can occur very delayed, sometimes only years after the irradiation.

diagnosis

The diagnostic process depends on the location of the necrosis. If it is an external necrosis, for example skin necrosis, a doctor can make a diagnosis after a closer look. In addition, the wound will be smeared to see if there are any pathogens in the necrosis. However, if the necrosis is internal, such as bone or organ necrosis, imaging is required. For this purpose, an MRI (magnetic resonance tomography) or a CT (computer tomography) is usually done. First impressions and a suspected diagnosis can also be made by performing an ultrasound of the affected area. However, more specific is a more complex imaging.

Stages of necrosis

In the case of necrosis, there is no general classification according to stages in medicine. A distinction is usually made according to the type and location of the necrosis. For example, a pressure ulcer is divided into four different stages (according to EPUAP). The depth of the wound and the involvement of certain structures play a role here. Necroses in the context of diabetic macroangiopathy ("diabetic foot") are also divided into different stages according to Wagner and Armstrong, whereby an existing infection also plays a role here, for example. In the case of bone necrosis, the ARCO classification is divided into seven stages. In particular, diagnostic criteria are taken into account.

Differences between necrosis and gangrene

Necrosis describes the death of cells as a reaction to damaging influences such as poisons, infections or insufficient supplies. This can affect a single cell or entire cell clusters. Necroses are divided into so-called “coagulation necrosis” (coagulation necrosis) and “colliquation necrosis” (liquefaction necrosis). Coagulation necrosis can develop in protein-rich tissues, with denaturing (destruction of the structure) of the proteins.

Gangrene describes a special form of coagulation necrosis. That means necrosis is a kind of umbrella term for various necrotic processes. A gangrene is in turn divided into a dry and a wet gangrene. While a dry gangrene appears very sunken and dried out and is therefore also referred to as "mummified" or leathery, a wet gangrene is slightly liquefied, shiny, purulent and smelly. The reason is the immigration and reproduction of bacteria, which liquefy gangrene through their metabolic products. Another special form is the so-called gas fire, in which an infection of the gangrene with clostridia (clostridium perfringens) leads to the formation of gaseous bacterial toxins.

Treatment / necrosectomy

Necrotic tissue has died, which means it cannot heal under any circumstances. However, remodeling can occur, with the necrosis falling off or being removed and new tissue growing back. This is particularly possible when the organ is very divisible, such as the intestine. In the case of skin necrosis, the healing process usually needs external support.

For this purpose, the dead skin (necrosis) is removed to prevent it from spreading and to make space for tissue that can grow back. This process is also called necrosectomy or necrectomy. This is done either surgically or through the use of emollient gels, acidic water, or even skin-eating maggots. In addition to the necrosectomy, a smear is also taken of the necrosis to test whether it is infected by pathogens. In this way, a therapy adapted to the respective type of bacteria or fungi can be carried out. Drug therapy with anti-inflammatory agents and blood circulation-enhancing drugs is also possible.

In addition to medical treatment, it is also important to protect the necrotic area and thereby support the healing process. For example, the patient should not lie down on the affected area, but relieve it. Sufficient exercise can also speed up the process, as it results in improved blood flow.

Duration of healing / prognosis

Similar to pain, the healing time and prognosis of necrosis depend very much on the situation and the patient. In the case of very superficial necrosis, it is possible to heal independently within a few weeks after eliminating the cause. However, if the necrosis is advanced, it is essential to consult a doctor. The prognosis then depends primarily on the patient's state of health.

A decubitus can often heal completely with sufficient rest and consistent relief. However, this can take several weeks to months, as the wounds often reach very deep and heal poorly. In the case of necrosis due to circulatory disorders, for example in smokers and diabetics, the healing depends primarily on whether these patients can eliminate the respective conditions under which the necrosis arose. The prognosis and the risk of recurrence are strongly tied to the risk factor. For smokers, for example, it is crucial whether they quit smoking and for diabetics it is important to regularly control their blood sugar and to counteract the disease as well as possible.

Necrosis of the foot / toe

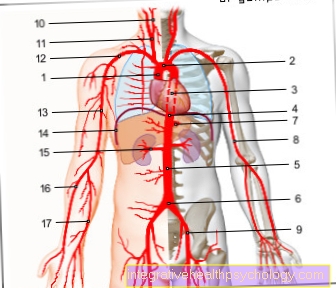

Feet, and especially toes, are very common areas of the body that are affected by necrosis. The reason for this is that they are very remote from the center of the body and are therefore very prone to circulatory disorders.

Read more under: Circulatory disorders in the legs

Foot and toe necrosis are particularly common in connection with the so-called "smoker's leg" and the "diabetic foot". In both cases, there is a reduced blood flow to the feet and thus an insufficient supply of oxygen. First of all, the toes are affected. If the necrosis continues, it spreads over the foot to the lower leg. If the diabetes is poorly controlled, separate necroses on the lower leg often occur.

Another common cause of necrotic toes is hypothermia or frostbite. Therapy of necrosis of the foot and toes is carried out by restoring adequate blood circulation. If this is not possible or if the necrosis is already too advanced, the corresponding part of the body may have to be amputated.

Necrosis of the heel

Necrosis of the heel is caused by so-called pressure necrosis. These are mainly found in people lying down and not very mobile and are also called pressure ulcers. When lying on your back, for example, there is permanent pressure on the rear heel. The supplying blood vessels are squeezed off and the tissue is not adequately supplied with oxygen, which subsequently leads to necrosis.

Pressure necrosis of the heel is also possible under other circumstances, such as constant standing or wheelchair users. This is treated by relieving the affected area. Depending on how advanced the necrosis was and whether deep wounds (ulcers) have already formed, a skin covering may also be necessary.

Achilles tendon necrosis

In the context of Achilles tendinitis or circulatory disorders of the Achilles tendon, parts of the tendon can die off. Such necrosis is manifested by severe pain and restricted mobility. Achilles tendon necrosis is usually diagnosed with an MRI, where the dead area is white. The treatment is performed by surgical debridement, i.e. the removal of necrotic tendon fibers. Depending on the extent of the disease and the surgically created substance defect, it may be necessary to strengthen the Achilles tendon with other muscle tendons in the body (e.g. plantaris tendon).

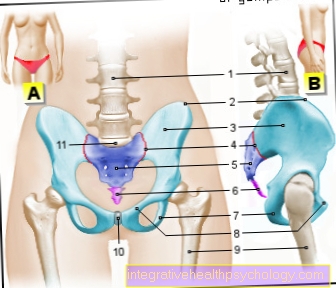

Tailbone necrosis

Similar to the necrosis of the heels, the most common cause of tissue sinking on the rump is also pressure necrosis. Since bedridden patients often lie on their backs for weeks and only move a little, positioning or mobilization by relatives, the nursing staff or the nursing staff is absolutely necessary.

The permanent pressure on the tailbone leads to a necrotic remodeling due to a lack of oxygen. In the long term this leads to a deep and poorly healing wound (ulcer). In the coccyx in particular, such a wound can take on extreme dimensions and be life-threatening for the patient. The reason is that the ulcer has a high risk of infection and at the same time there is hardly any tissue between the skin and bones, so that its involvement is often observed.

Necrosis from wounds

Various mechanisms can lead to necrosis in wounds. Overall, however, this rarely happens. One possibility is that the damage to the skin can lead to a defect in the blood supply and thus to an insufficient supply of oxygen.

Necrosis caused by the immigration of pathogens such as bacteria is also possible. Bacterial causes thrombosis (formation of blood clots) of the blood vessels and reduced blood flow.

Another option is that the mechanical impact that caused the wound has already resulted in a low number of cell necrosis. This releases inflammatory mediators and kills more cells, allowing the necrosis to spread. People with a weakened or suppressed immune system are particularly at risk.

Necrosis of the skin

Skin necrosis is much more common than bone or organ necrosis. They occur mainly in the form of pressure ulcers, circulatory disorders or frostbite. All of these forms have in common that the tissue is insufficiently supplied with oxygen. The cells become acidic, die and eventually burst.

Necroses only become visible to humans when entire cell aggregates within the tissue die. Externally, necroses appear yellowish-grayish-black in color and are usually very dry and sunken (leathery). In addition, there is often an inflammation of the surrounding tissue, which then reddens, swells, becomes warm and hurts. The necrosis itself is mainly painful because of the lack of oxygen. However, often this is not noticed by the patient because the necrosis progresses very slowly or there is a decreased sensation.

Necrosis of the skin is treated by surgically removing it and treating wounds in a conventional manner. In addition, antibiotic therapy and anti-inflammatory drugs are usually given.

A special form of skin necrosis is necrotizing fasciitis, which is caused by bacteria. If this occurs in the genital region, it is called Fournier gangrene.

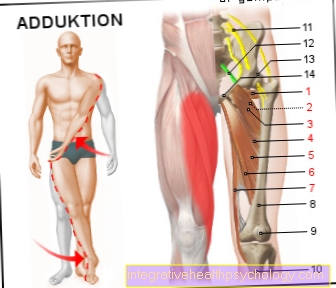

Femoral head necrosis

In femoral head necrosis, also called femoral head necrosis, bone tissue in the head of the thigh bone dies. Femoral head necrosis is usually a circulatory disorder. The reason is that the femoral head is very complicated and supplied by various small blood vessels. The necrosis usually occurs sporadically (accidentally), but can also result from traumatic events (accidents) or in the context of influences that reduce blood flow, such as diabetes, alcoholism or smoking. Necrosis of the femoral head manifests itself as stress-dependent pain in the groin, which, however, also occurs at rest.

A femoral head necrosis is usually diagnosed with an MRI (magnetic resonance tomography). The therapy depends primarily on the age and everyday demands of the patient. The hip joint is often replaced by a prosthesis, a so-called hip TEP, which completely eliminates the necrosis, but is not quite as resilient as an original hip and has to be replaced again after around 15 to 20 years. For younger patients, there are other options, such as drilling the necrosis or replacing the necrosis with stem cells from the femur. For less advanced femoral head necrosis, drug therapy with drugs that stimulate blood circulation is also possible.

Femoral head necrosis can also develop in the context of Perthes' disease, which should not be confused.

Read more on the subject at: Femoral head necrosis

Necrosis on the finger

Similar to the toes and feet, the human fingers are also very remote from the center of the body. Therefore, they are particularly likely to be affected by necrosis. Here too, hypothermia and frostbite play an important role. The vessels that supply the fingers with blood and oxygen have a small diameter and are therefore particularly sensitive.

In addition to diabetes, which plays a particularly important role in the legs and feet, smoking in particular is a risk factor for necrosis of the fingers. Smoking reduces blood circulation in various ways and leads to necrosis of the extremities in the long term.

More rarely, other circulatory disorders such as "Raynaud's syndrome" can also be responsible for necrotic fingers.

Aseptic necrosis

“Aseptic” refers to the absence of septic factors such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and prions. Aseptic necrosis can therefore occur in any aseptic part of the body.

In medicine, however, aseptic necrosis is a kind of umbrella term for bone necrosis, which is usually caused by a reduction in blood flow. Possible causes are long-term therapies with cortisone or bisphosphonates, chemotherapy, radiation, work in compressed air areas, sickle cell anemia, Gaucher's disease or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The blood vessels supplying the bones constrict or close and the bone dies. Typical complaints are pain and restricted mobility. Bone necrosis is divided into different degrees of severity and the respective medical name of the necrosis depends heavily on the affected section of bone.

Read more on the subject at: Bone necrosis

Muscle necrosis

A distinction is made between ischemic and iatrogenic muscle necrosis. Ischemia is a condition of insufficient oxygen supply in the tissue. In ischemic muscle necrosis, the blood vessels that supply the muscles are usually blocked or damaged. The lack of oxygen in the muscles can lead to a so-called compartment syndrome. The swelling of the cells leads to a narrowing of the muscles within the fascia. As a result, other vessels are pinched off and severe pain occurs. Iatrogenic muscle necrosis can result from intramuscular injections.

Pulp necrosis

The tooth pulp is located inside a tooth and contains the nerves and blood vessels that supply the tooth. In the case of pulp necrosis, the dental pulp becomes inflamed, for example due to the invasion of bacteria. This leads to a swelling of these, which leads to a pressure on the blood vessels and severe pain (pressure on nerves). The reduced blood flow to the pulp leads to an insufficient supply of oxygen and death of the cells (necrosis). Pulp necrosis is treated by drilling open the tooth. This will reduce the pressure and restore blood circulation.

Necrosis of the gums

Necrosis of the gums usually occurs in the form of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) or necrotizing ulcerating periodontitis (NUP) and requires urgent treatment, otherwise there is a risk that the infection will spread to the bones.

In contrast to the NUG, in which only the gums (gingiva) are affected, in the NUP the infection has already passed on to the periodontium (paradontium) and is therefore more advanced and more threatening.

Both diseases manifest themselves as sudden, severe pain, sores, bleeding and reddish-gray discoloration. Gum necrosis can be prevented through adequate oral hygiene, avoiding tobacco consumption and strengthening the immune system.

Necrosis in the jawbone

Pine necrosis is caused by the death of the jawbone, which means that it is usually open and visible when the oral cavity is viewed. Pine necrosis is caused, for example, by inflammation or injury to the jawbone and often does not heal very well. In the last few years in particular, the iatrogenic (medical-related) development of pine necrosis has become more and more relevant. For example, radiation and chemotherapy play a major role in cancer treatment in causing bone necrosis. Bisphosphonates, which are used in osteoporosis, can also cause necrosis of the jaw and are therefore primarily prescribed in palliative medicine.

Read more about the topic here: Biphosphonate-associated bone necrosis